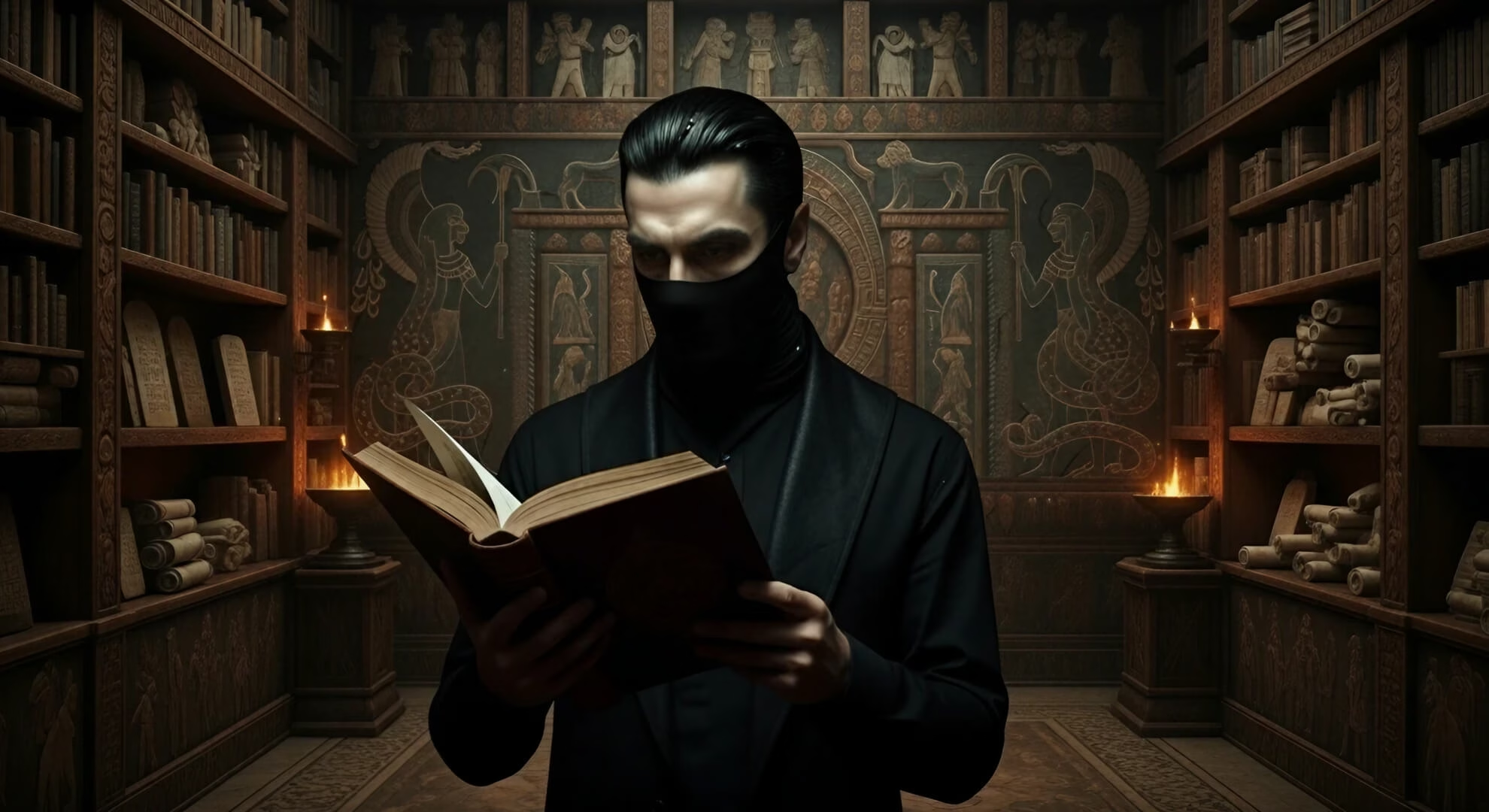

The mind is not a palace, but a scriptorium. It is a vast and solitary chamber, built not of stone, but of consciousness itself. Within its walls, there is only one work of consequence: the singular, illuminated manuscript of a life, a tome to which pages are added by candlelight, but from which none may ever be removed. I am its sole inhabitant, its author, and its sworn archivist.

My adversary is not an active aggressor, but a presence inherent to the scriptorium itself. It is the dust in the air, the humidity in the stone, the silent, slow-acting acid of time.

It is an entropy that works without malice and without rest. It does not tear the pages; it merely thins the vellum. It does not burn the book; it simply fades the ink.

Its victory is not declared in a moment of violence, but achieved in the quiet, creeping transformation of a clear, black line into a faint, grey ghost.

This fading is not a gentle departure; it is a quiet amputation. A memory does not simply vanish; it leaves behind a phantom, a hollow space in the narrative that still aches with the ghost of its presence.

At times, it is a sudden coldness, the realization that the face of a loved one has lost its sharp definition in the mind’s eye. At others, it is a subtle corruption, where the pure, resonant sound of a past joy now reaches the ear as a distant, tinny echo, stripped of its original warmth.

This antagonist has no will, yet its work is absolute. It seeks the corruption of the text, the slow warping of the narrative until the original account is lost to interpretation, then to speculation, and finally, to the void. It is a force that turns crisp, factual histories into malleable myths.

Therefore, my existence has become an act of ceaseless curation. Every memory must be revisited, every page inspected for the first signs of the fade. It is a task of profound, monastic devotion.

I am the scribe-in-chief, holding the line against the decay not with a sword, but with a pen. The work is not to prevent the damage—for that is impossible, but to counteract it.

My tools are not merely of ink and recollection. I wield the harsh, clarifying light of introspection, holding a fragile page up to its glare to expose the faintest watermarks of self-deception. I employ the solvent of critical analysis, carefully dissolving the grime of nostalgia that can obscure a difficult truth.

Each memory is cross-referenced, collated, and footnoted with the hard-won context of the present. This is not passive remembrance; it is the rigorous, scholarly work of maintaining the one true text.

The most insidious work of this entropy is the creation of the palimpsest. It does not always efface a text completely; often, it renders it just faint enough for a new, false narrative to be written over it.

A memory of triumph can be subtly overwritten with the language of doubt. A moment of clarity can have its margins filled with the scribblings of regret. The archivist’s greatest duty is one of intellectual honesty: to hold the page to the light and distinguish the foundational ink from the latter-day overpainting.

More dangerous than the slow fade, however, is the work of the forger within. This is the aspect of the self that is not content to be an archivist, but seeks to be a propagandist.

It is a saboteur that moves through the stacks in the dead of night, seeking to insert pages of pure invention, to burnish a tarnished memory with unearned gold leaf, or to excise a moment of shame entirely.

To fight the slow acid of time is a noble battle, but to fight the part of oneself that actively seeks to lie to itself—that is the archivist’s secret, most desperate war.

Now, however, a terrible new synchronicity is at work. The decay of the physical canvas has breached the walls of the scriptorium. The antagonist is no longer merely an entropy that fades the ink, but an attrition that attacks the scribe.

The tremor that once merely marred a line on a page now threatens the act of writing itself. The very nerves that allow the archivist to turn a page, to hold a pen, to give voice to the words written there, are becoming an unreliable medium.

This transforms the work from curation to a desperate act of transcription. It becomes a race to commit the most vital passages to an immutable form before the physical lexicon—the voice, the hand, the very breath—is lost.

The scriptorium, once a fortress of sovereignty, now risks becoming a silent museum, its collection perfectly preserved but locked away from the world, its archivist a prisoner within his own library.

The ultimate act of mastery, then, becomes one of triage: to know which memories are the load-bearing walls of the soul, and to reinforce them, ensuring they are the last to fall.

Yet, this constant vigilance has forged an unexpected mastery. The scriptorium may be subject to the laws of decay, but the mind of the archivist remains a sovereign territory.

Time can fade the ink upon the page, but it cannot touch my memory of what was written.

The manuscript itself may become fragile, but my understanding of its meaning—the intricate cross-references, the hidden themes, the subtle foreshadowing—grows more resilient with every inspection.

The library may be crumbling, but its catalog is perfect, and it resides within me.

This has conferred upon me a unique form of alchemy. When I discover a passage that has grown faint, I do not merely lament its loss. I take up my own pen and re-scribe it. But I am not the same man who first wrote it.

The act of preservation becomes an act of reinterpretation.

I trace the old lines, but my present knowledge informs my hand. I restore the memory, and in doing so, I deepen it, lending it the wisdom of the archivist who has read the entire book, who knows how the story ends.

The loss of a page, therefore, is more than a bereavement; it is a clearing. The void it leaves is not an absence, but a fallow ground upon which a new structure can be erected.

To lose the memory of a past failing is to be liberated from its architecture of shame, compelling me not to rebuild what was, but to build what can be. This is the paradoxical gift of the fade: it is the architect of a constant, necessary renewal.

This erasure extends beyond the self. Faces, once heavy with the accumulated sediment of a shared history, are rendered new.

The text of my judgment is wiped clean, forcing me to read the person before me as they are in the present moment—a fresh manuscript—unless the original page was so deeply scarred by the ink of trauma that its ghost remains, a permanent watermark of caution.

The final tome, when the scriptorium doors are sealed, will not be a pristine, unblemished text. That was never the objective.

It will be a chronicle of the struggle against oblivion. It will show the original script, the marks of the slow fade, and the defiant, hard-pressed lines of my own restorative hand.

It will be a book that tells not only the story of a life, but the story of what it took to keep that story from being erased.

For every library is subject to the slow work of decay; it is the archivist’s choice whether that decay becomes the final word, or merely the fragile vellum upon which a more profound and honest history is written.