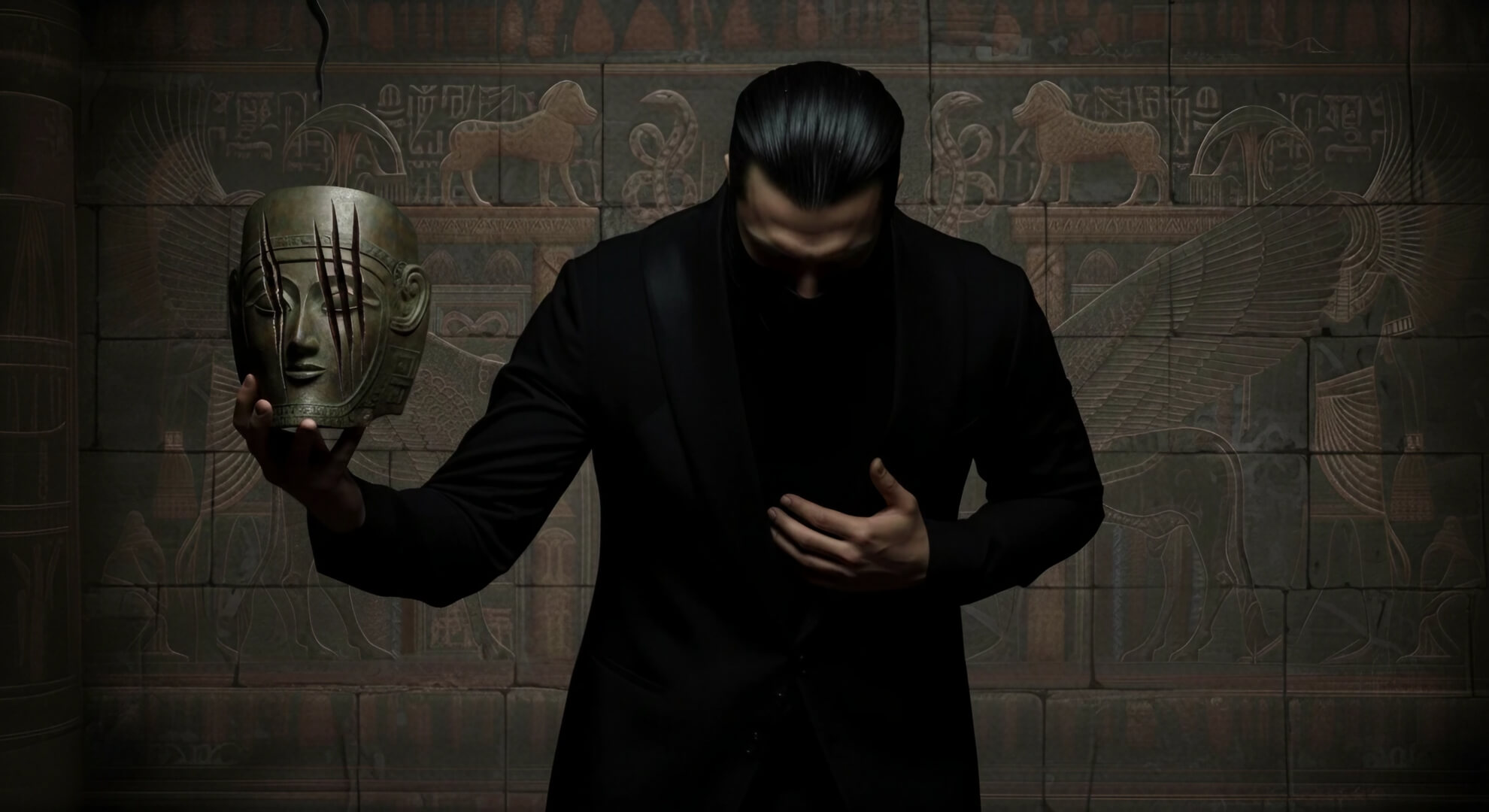

The scriptorium holds the past, the forge shapes the will, but neither is built for an audience. To engage with the world is to leave the silent workshop and step onto a stage. The self, in its raw, unadorned state, is not a viable actor. It is too complex, too volatile, too true. The world does not demand truth; it demands a performance. And for every performance, there must be a mask.

I am the dramatist of this theater, and its sole occupant. It is in the silent, backstage spaces of the mind that the true work is done.

Here, I am the architect of my own role, the designer of my own costume. The mask I present to the world is not an act of deception, but of translation. It is a necessary simplification, a functional effigy crafted to be legible to an audience that cannot, and must not, be allowed to read the full, intricate text of the self.

The adversary in this theater is not a villain on the stage, but the audience itself. It is the relentless, collective gaze that seeks to flatten the actor into the role. It is the thousand assumptions and projections that beat against the mask, attempting to fuse it to the skin.

The audience’s greatest desire is for the performance to be real, for the character to be the man. Their applause is a form of erosion, a constant pressure to forget the quiet, sovereign self who waits in the wings.

To yield to this pressure is the ultimate defeat: to become a player who has forgotten he is acting, a king in greasepaint who believes his own decree.

This animosity is not born of misunderstanding, but of clarity. I look upon the modern stage and see a grotesque theater of vanity, a frantic masquerade where hollow men and women don the masks of happiness and virtue to appease one another.

Theirs is a world built on the shared illusion of meaning, a spectacle I have long since rejected. My performance, therefore, is not an act of participation in their charade. It is the calculated engagement of an ambassador from a sovereign nation, interacting with a foreign court he finds fundamentally corrupt.

My mask is not designed to join them, but to enforce a quarantine of the soul. It is a face of deliberate menace, crafted to impose a chilling distance, to project an aura of quiet lethality—a warning that to approach too closely is to trespass on ground where their illusions hold no power, and carry a mortal risk.

This mask was not crafted from choice, but from necessity. Its design is dictated by the raw material of the other domains.

The scars from the canvas are not hidden; they are incorporated into its features, the fine, painted lines of a tragic character. The metal plates beneath the skin provide its rigid, unyielding structure.

The face, its very substance hardened and rendered immobile, is not a flaw in the actor, but the very foundation of the mask’s design—a permanent, unsmiling visage that holds the audience at a perfect, analytical distance.

The forge, therefore, has a new purpose. It is not only for the forging of internal tools, but for the maintenance of this external face.

Each dusk, the mask is heated, beaten into shape, and meticulously prepared. The tremor in the hand is not a weakness, but the subtle, humanizing imperfection in the performance.

The sleepless fire from the trapped nerves is the secret energy that fuels the character’s intensity. The monster I see in the crucible is the raw material for the role the world sees on the stage. It is the ultimate alchemy: to take the face of a monster and, through sheer force of will, craft it into the mask of a philosopher.

The greatest danger is not that the audience will see through the mask, but that the actor will forget he is wearing it. The performance must be flawless, but it must never be total. Therefore, I have cultivated a discipline of duality.

There is the self who speaks, who moves, who engages with the script of the world. And there is the silent witness, the true self, who resides in the inviolable darkness backstage, observing, directing, and remembering. This inner self is the anchor that holds the actor to his purpose.

He is the one who knows the performance is a tool, not a truth; a function, not a soul.

Yet, this duality is not a clean partition of the soul, but a permeable membrane. No performance is without its residue.

The emotions summoned for the stage, even when conjured by pure technique, leave their faint, indelible echoes in the quiet backstage.

The architect may observe, but he observes through the actor’s eyes. The sovereign self may direct, but the voice he uses to command himself is subtly altered by the timber of the character he plays.

The true, unspoken terror is not that the audience will see through the mask for the man, but that the man, in his silent chamber, will begin to mistake his own reflection for the mask.

The victory, then, is not in a convincing performance. It is not in the applause, nor in the acceptance of the audience.

The victory is in the quiet moment at the end of the day, when the theater is empty, the lights are extinguished, and the mask is removed. It is in the silent acknowledgment between the actor and the self that the role was played, but the soul remained sovereign.

The highest art is not to wear the mask well, but to never forget the silence of the face it conceals.